The Moment of Zoho

India’s homegrown tech story has found an unlikely hero in Zoho. For nearly three decades, this Chennai-based SaaS company quietly built enterprise-grade software used by millions worldwide—often flying under the radar until recently. The tide shifted when ministers and policy leaders began signaling support: IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw publicly endorsed Zoho’s stack and Home Minister Amit Shah’s shift to Zoho Mail took headlines, marking a rare pivot—an official validation of “swadeshi tech” at the national stage.

This moment is remarkable not just for its symbolism, but for what it represents: Zoho isn’t a flash-in-the-pan startup chasing headlines or venture hype. It’s a 28-year-old, billion-dollar-plus software powerhouse that has never raised a rupee from investors. Now, as India’s sovereign technology ambitions gather force, Zoho stands at the center of a high-stakes discussion—not just as a mascot for self-reliance, but as a mature challenger to global software titans.

Decades before Zoho became the poster child for “software made in India,” it emerged in 1996 as AdventNet in California, founded by Sridhar Vembu and Tony Thomas. The early focus was on network management tools for telecoms and enterprises, a niche but vital area.

A turning point arrived in 2004, when Sridhar Vembu made what appeared a counterintuitive move: he shifted R&D not to Bengaluru or Hyderabad, but to Tenkasi—a small Tamil Nadu town. This relocation didn’t just shape company operations; it became the philosophical anchor for Zoho’s future. The formula: build quietly, prioritize independence, and let results speak louder than hype.

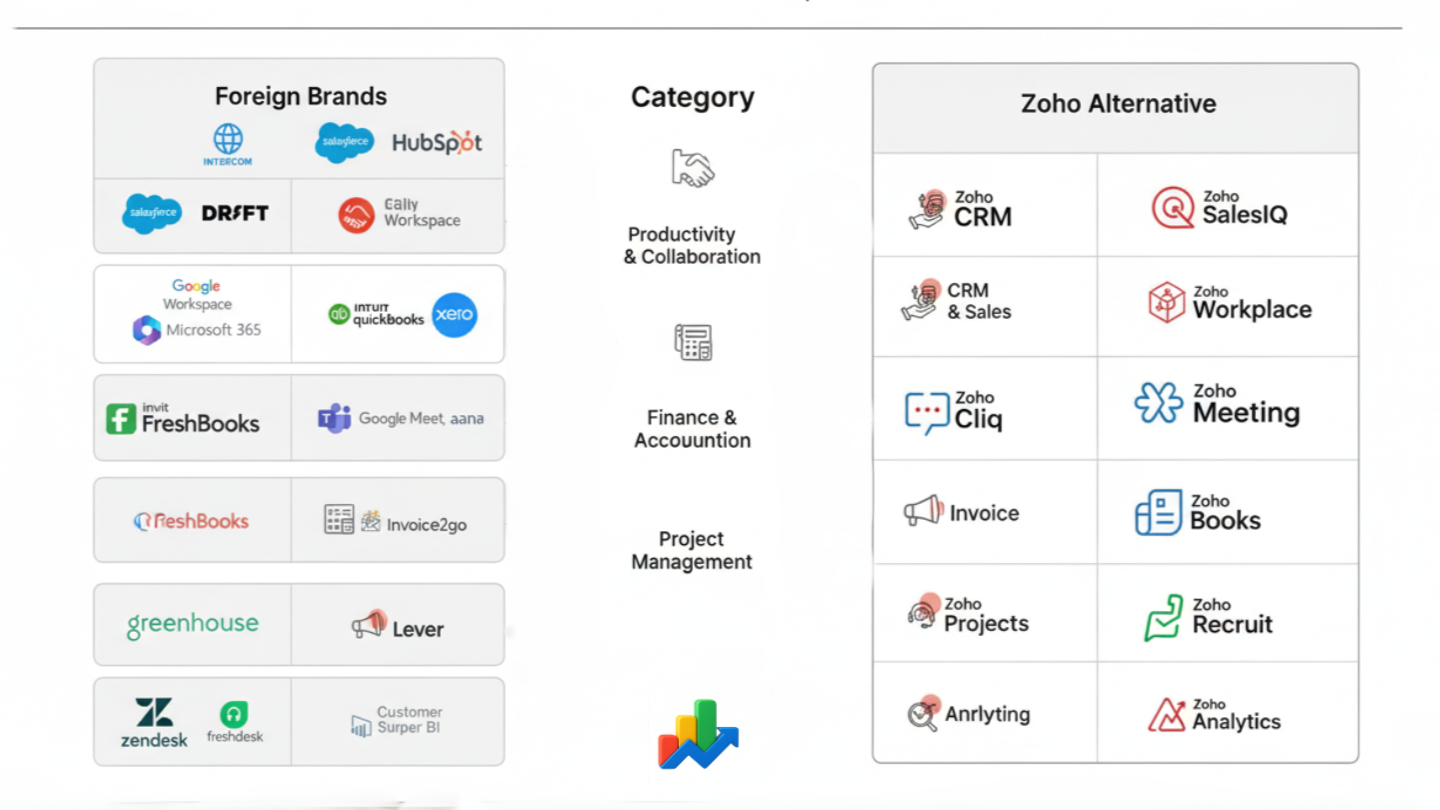

As the global tech world raced into the cloud in the mid-2000s, AdventNet evolved and rebranded as Zoho. The first SaaS launches—Zoho Writer, CRM, Projects, and Mail—set the groundwork. While most homegrown Indian firms were still focused on IT services and backend outsourcing, Zoho bet big on a unified operating system for business, an all-in-one SaaS ecosystem.

Fast forward: Zoho today offers over 50 integrated apps, serves more than 100 million users in 180+ countries, and has a workforce exceeding 10,000. Most astonishingly, every milestone was reached with no venture capital, a rarity that stands out in the hyper-funded SaaS universe.

Zoho’s story is inseparable from Sridhar Vembu’s philosophy. No venture capital. No unicorn theatrics. Instead, Zoho has crafted a unique talent pipeline with its Schools of Learning—directly training high school graduates and rural youth for its tech teams.

This model did more than manage costs; it decentralized opportunity and sent the company deep into rural India. Continuous reinvestment into R&D—not aggressive marketing—meant that Zoho survived cycles and fads that tripped up peers. Its independence is less a financial footnote and more a statement on what sustainable, inclusive technology can become.

For years, Zoho ran in the background, competing quietly with Microsoft, Salesforce, and Google. But the period of 2024–2025 transformed its relevance dramatically.

With global anxieties on data sovereignty and digital self-reliance peaking, Zoho’s template was suddenly in demand. The company operates its own data centers, pays taxes on global revenues locally, and builds every part of its stack—hardware and software—in India. The end-to-end, homegrown logic became a national advantage, something earlier “digital nationalism” efforts couldn’t pull off at scale or credibility.

Among Zoho’s quiet successes, Arattai stands out for its symbolism. Originally launched in 2021, Arattai rapidly gained traction after India’s top officials began using it in 2025. Sign-ups went from a modest 3,000 per day to 350,000 in days.

Unlike global rivals, Arattai is built on privacy—ad-free, no data monetization, full end-to-end encryption. Its anticipated UPI integration sets it up as the country’s first messaging-plus-payments platform coded entirely within Indian borders. Whether or not Arattai scales internationally, its domestic influence as a “sovereign app” is pushing the boundaries of homegrown innovation.

Zoho’s ambitions widened in 2025 at the Global Fintech Fest, where it introduced a suite of POS terminals, QR soundboxes, and integrated payment systems. The company already helps millions of SMEs run their finances and CRM; now, by bringing billing, transactions, and management under one hood, Zoho is taking on entrenched Indian fintechs like Paytm and Razorpay.

Yet, Zoho has something these fintechs do not: direct access to business data and process workflows, thanks to its existing software base. This seamless integration could change how India’s small businesses handle money—fully within one unified suite.

While AI dominates the global tech narrative, Zoho is carving a distinct approach—rooted in Indian realities. In 2024, it launched Zia, a large language model fine-tuned for real-world business use: summarizing data, automating workflows, extracting insights, and even facilitating code generation. The debut of Vani, a collaborative AI suite, further reflects this focus.

Zoho’s bet: Make AI infrastructure local, business-targeted, and, above all, sovereign. Instead of competing directly with Western LLM giants, Zoho aims to ensure Indian companies have access to private, India-trained AI on Indian infrastructure.

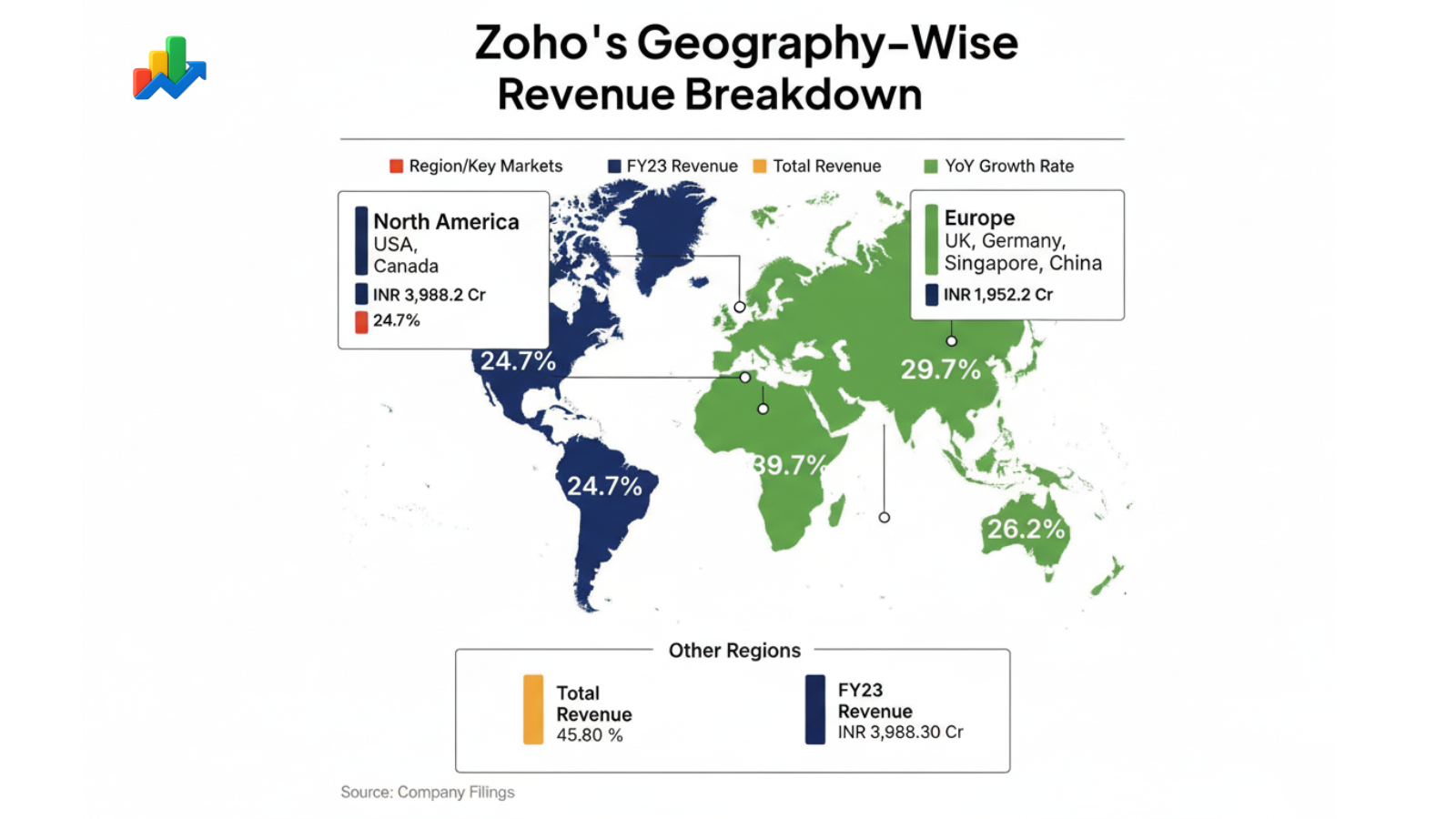

Even as Zoho draws 70% of its revenues from North America and Europe, India has become its most dynamic growth market in recent years. Small businesses and startups hungry for cost-effective, trustworthy software are flocking to Zoho—drawn by features like UPI, multi-language support, and strict local data policies.

India, for Zoho, is no longer just origin or base. It’s the high-potential growth market that could make Zoho’s vision for a sovereign, business-grade technology stack a new global benchmark.

Still, challenges remain. Uprooting global ecosystems built by Microsoft, Salesforce, or Google—each with vast budgets and mature partnerships—won’t happen overnight. Zoho’s products, while robust, sometimes lack the global polish and brand recall of its Western counterparts. Its preference for self-funding naturally dictates a steadier, more measured growth trajectory.

But in a world beset by overvalued, high-burn tech companies, Zoho’s steadiness and depth may be a long-term asset. The company’s narrative is built around trust, not flash.

Ultimately, Zoho is more than just a business-software story. It’s a living model of what ethical, inclusive, and patient Indian innovation can achieve—from tier-2 towns to world markets. It offers a fresh template: one emphasizing not just technical excellence, but sovereignty, social responsibility, and genuine independence.

While comparisons to Microsoft are inevitable, Zoho is on a path to build something culturally and structurally different—rooted in Indian values and realities, yet globally relevant.

Zoho is proof that world-class technology can be built quietly, with integrity, and entirely on Indian soil. In an industry obsessed with valuations and rapid exits, Zoho’s defining achievement is far rarer: true independence. And that, more than any headline or funding milestone, may be its greatest legacy.