Warren Buffett changed investing by proving that disciplined value investing, patient ownership of great businesses, and intelligent use of insurance “float” could beat the market over decades, turning a dying textile mill into a trillion‑dollar conglomerate. His looming retirement as Berkshire Hathaway’s CEO and the handover to Greg Abel now raises a crucial question: can this philosophy and culture outlive its creator in a tech‑driven, index‑fund world?

Buffett grew up obsessed with money and business, selling newspapers, chewing gum, and tracking stock prices as a teenager before studying under Benjamin Graham at Columbia Business School. Graham’s teaching on buying companies for less than their intrinsic value became the foundation of Buffett’s entire career and the playbook he refined for modern value investing.

When Buffett first bought Berkshire Hathaway, it was a struggling New England textile mill that he could have treated as a short‑term “cigar butt” investment, but he instead used the corporate shell and cash flows as a platform to acquire better businesses. Over decades, that platform evolved into today’s Berkshire Hathaway, which owns or controls railroads, utilities, insurers, manufacturing firms, consumer brands like Dairy Queen, and an enormous listed‑stock portfolio.

Buffett’s core breakthrough was to blend Graham’s bargain‑hunting with Charlie Munger’s push toward “wonderful businesses at fair prices” rather than just cheap stocks. Instead of speculating on short‑term price moves, he evaluates what a business will likely earn over 10–20 years, then buys only when the market price offers a margin of safety against that long‑term estimate.

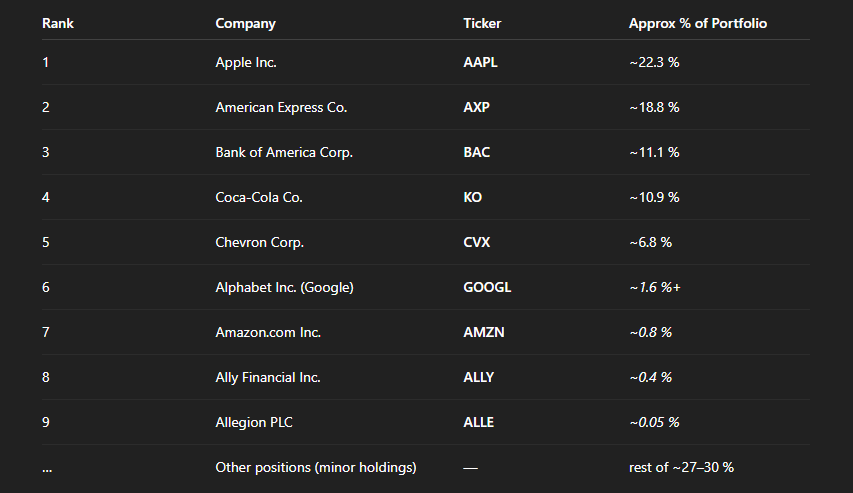

His American Express investment is a classic case study: he bought heavily when the stock was depressed by scandal, but the underlying brand, cardholder loyalty, and payments network remained powerful. Berkshire built its current core Amex stake largely in the 1990s for about 1.3 billion dollars, and by holding it for decades as the brand compounded value, that stake became worth tens of billions.

Central to Buffett’s approach is the idea of an “economic moat” – any durable competitive advantage that protects a business’s profits from competition. In American Express, the moat comes from its premium brand, affluent customer base, and the closed‑loop network built around their spending, which is difficult for competitors to replicate.

Buffett also favors businesses where regulation and capital intensity create barriers to entry, such as energy and utilities. By buying and building regulated energy and infrastructure assets inside Berkshire, he assembled a collection of businesses that competitors cannot easily copy, reinforcing the conglomerate’s resilience.

Perhaps Buffett’s most underappreciated innovation is how he used insurance “float” as a permanent, low‑cost source of investment capital. Policyholders pay premiums today for claims that may be paid years in the future, and as long as underwriting is disciplined, insurers hold large pools of money that “don’t belong to them” but can be invested meanwhile.

Through acquisitions and growth in its insurance arms, Berkshire scaled this float dramatically and then invested it in stocks, bonds, and whole businesses, creating an internal engine of leverage without traditional debt. This structure turned boring insurance subsidiaries into a powerful funding source, influencing many private equity and alternative asset managers to pursue similar insurer relationships in recent years.

Charlie Munger, Buffett’s long‑time partner, reshaped Buffett’s evolution from cigar‑butt investor to owner of elite franchises. At Berkshire’s annual meetings, their candid banter and shared reasoning about businesses became a major attraction, drawing investors from around the world to Omaha each year.

Munger pushed Buffett to focus on companies with durable advantages and strong brands, such as Coca‑Cola and Bank of America, rather than cheap but mediocre businesses. This shift elevated Berkshire from a collection of statistical bargains into a powerhouse of high‑quality holdings, aligning the portfolio with long‑term compounding rather than short‑term reversion.

Despite his track record, Buffett has openly admitted serious mistakes, which is itself part of his legacy. One high‑profile error was Berkshire’s stake in IBM in the early 2010s, where he underestimated how quickly the industry would rotate toward cloud computing and away from IBM’s traditional strengths.

Another challenge has been the Kraft Heinz merger, which struggled under changing consumer tastes toward healthier options and the impact of inflation on its business model. Buffett has acknowledged that, in hindsight, the deal was not ideal and that simply reversing the merger would not fix deeper structural issues, illustrating his willingness to own misjudgments rather than rewrite history.

Buffett’s personal lifestyle has reinforced his credibility as a steward of capital: he still lives in the same Omaha house he bought decades ago, frequents McDonald’s locally, and has long taken a relatively modest 100,000‑dollar salary as CEO. That contrast between wealth and simplicity strengthens the perception that his decisions are driven by rational capital allocation rather than personal extravagance.

Culturally, he built Berkshire around trust, decentralization, and rationality: managers run their businesses with minimal interference, and capital is allocated from headquarters based on opportunity, not politics. This culture, plus decades of market‑beating returns versus benchmarks like the S&P 500, made Berkshire a kind of secular “Hall of Fame” for long‑term investors.

In recent years, Berkshire has struggled to find enough compelling opportunities for its ever‑growing cash pile, which now exceeds 300 billion dollars. It is vastly easier to find great mispriced bets when managing 100–200 million dollars than when trying to deploy hundreds of billions without diluting returns.

Higher interest rates have at least turned that idle cash into a substantial income stream, giving Berkshire a safe yield while it waits for better opportunities. Yet the sheer size of the capital base means each incremental investment must be large to move the needle, making the classic Buffett style of buying mid‑size bargains harder to execute.

Note: Values and weights are approximate and based on 2025 disclosures; this is not a complete list of every holding.

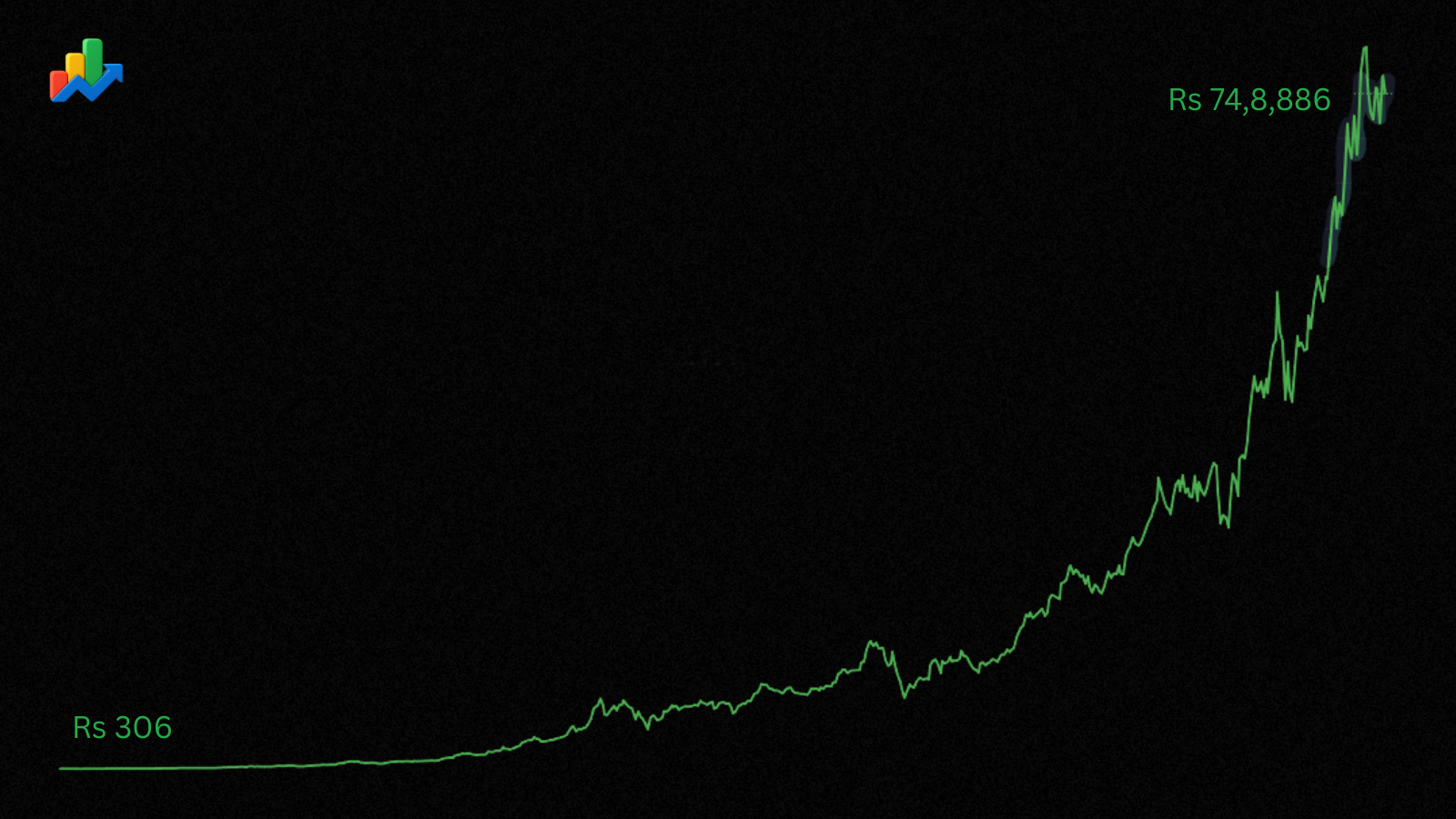

Berkshire Hathaway’s Class A stock chart shows one of the most extreme examples of long‑term compounding in market history, with the share price rising from roughly 300 dollars in its early decades to around 748,000 dollars today, turning what once looked like a modestly priced industrial company into a trillion‑dollar conglomerate and vividly illustrating how decades of reinvested earnings, disciplined capital allocation, and consistent outperformance versus the broader market can translate into a near‑vertical price curve on a long‑term graph.

Buffett, now 95, plans to retire as Berkshire’s CEO at the end of 2025, with Greg Abel set to take over leadership of the roughly 1.2‑trillion‑dollar enterprise. Abel has run Berkshire’s energy operations for years, giving him deep experience with regulated businesses, long‑term capital projects, and the decentralized Berkshire culture.

Buffett will remain as chairman and a major shareholder, though he is gradually transferring his stake to his children’s foundations, so his influence will continue even as day‑to‑day responsibilities shift. Abel will also assume duties like writing Berkshire’s widely read annual shareholder letter and presiding over the annual meeting, both of which have long been signature platforms for Buffett’s philosophy and personality.

Abel inherits Berkshire at a moment when classic value investing is under pressure from a market often led by high‑growth technology companies with lofty valuations. While Buffett has invested in tech in recent years, his missed early moves in some technology names and the dominance of fast‑growing platform businesses have sparked debate about how adaptable Berkshire’s approach is to a software‑ and data‑driven world.

At the same time, the conglomerate model itself faces scrutiny, as many diversified giants like General Electric have been broken up in recent years. Berkshire’s continued success will test whether a well‑run conglomerate anchored in disciplined capital allocation, strong operating businesses, and a fortress balance sheet can remain relevant in an era of specialization and passive index investing.

Buffett’s influence extends far beyond Berkshire’s balance sheet; he shifted how both professionals and individuals think about stocks. His example helped popularize the view that stocks are ownership in real businesses, not trading tickets, and that the combination of patience, discipline, and rational analysis can create enduring wealth.

He also offered a living counterexample to the idea, embodied by large index‑fund providers, that “no one can beat the market,” by consistently outperforming major benchmarks over decades. Even for those who choose low‑cost index funds, the emphasis on fees, long time horizons, and staying within one’s circle of competence owes a clear debt to Buffett’s teachings and public communication.